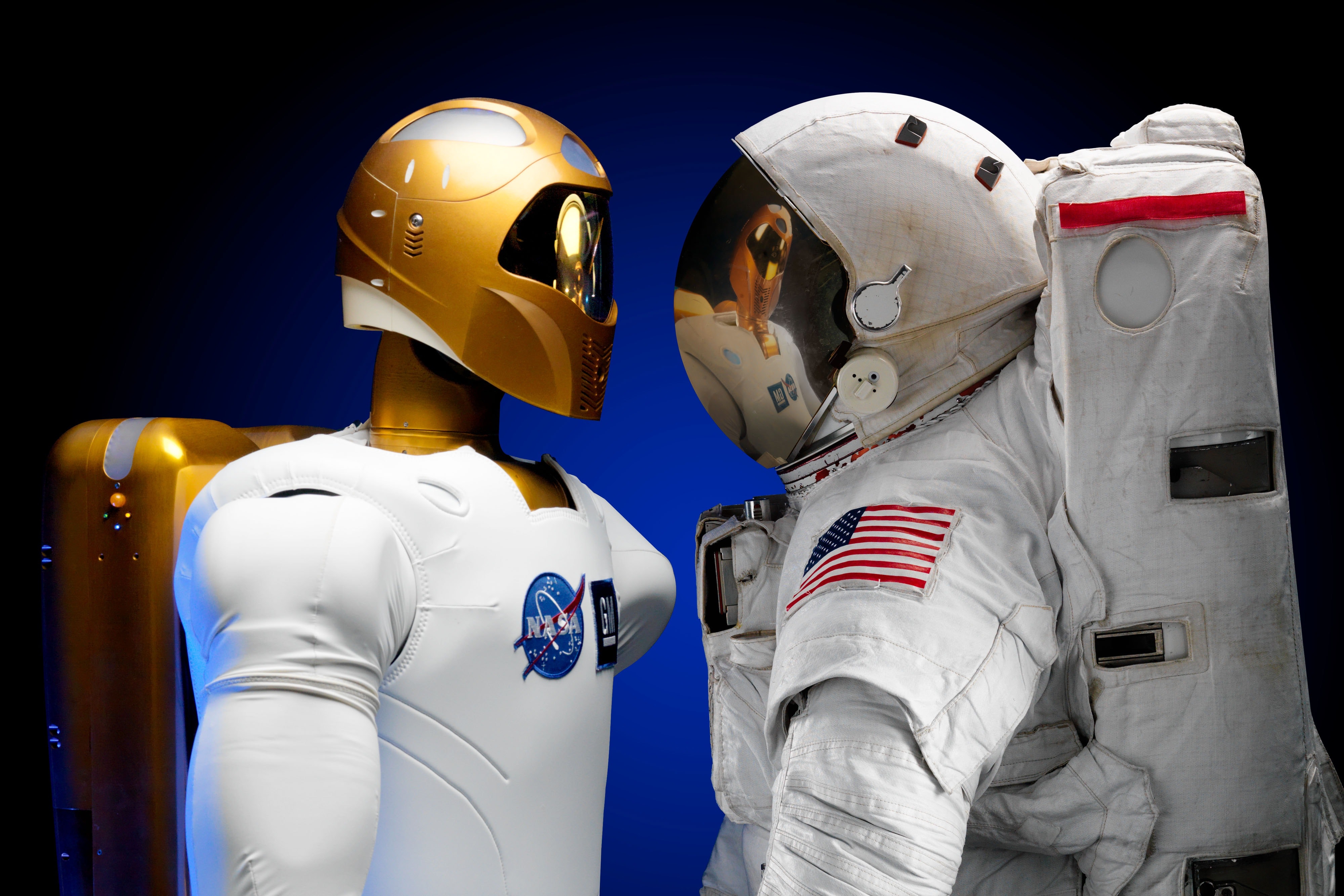

How to Create a Mind – Ray Kurzweil

The Structure

“How to Create a Mind” is the latest nonfiction book by Ray Kurzweil as of today. It starts technical and shifts toward the philosophical aspect of a mind. After a brief introduction to the nature of thinking, the author moves to use cases of the Markov model in the speech recognition systems based on Siri and IBM’s Watson examples. Kurzweil also elaborates on the history of computing from the very first algorithms from the 18-th century, through Turing machine and the works of John von Neumann, which laid the foundations for the current machines. Few next chapters touch are dedicated to neocortex part of the human brain and the ability to reproduce the pattern-recognition ability in a digital form. The remaining part is purely philosophical but in a good way.

The Essence

It’s the mind. Observed from different angles. Most of the examples included in this book are stimulating, such as the experiments with split-brain patients and the reasoning about a false cause. In short, split-brain is a syndrome in which the two cerebral hemispheres get disconnected. It turns out that even though the hemispheres cannot communicate with each other, which means that patients live with two separate brains, subjects may function normally. However, since the hemispheres are cross-connected (left hemisphere is connected to the right part of the body and vice-versa), limiting brain inputs to one of the hemispheres bring some unexpected results.

The left hemisphere in a split-brain patient usually sees the right visual field, and vice versa. Gazzaniga and his colleagues showed a splitbrain

patient a picture of a chicken claw to the right visual field (which was seen by his left hemisphere) and a snowy scene to the left visual field

(which was seen by his right hemisphere). He then showed a collection of pictures so that both hemispheres could see them. He asked the patient

to choose one of the pictures that went well with the first picture. The patient’s left hand (controlled by his right hemisphere) pointed to a picture of a shovel, whereas his right hand pointed to a picture of a chicken. So far so good—the two hemispheres were acting independently and sensibly.

“Why did you choose that?” Gazzaniga asked the patient, who answered verbally (controlled by his left-hemisphere speech center), “The chicken

claw obviously goes with the chicken.” But then the patient looked down and, noticing his left hand pointing to the shovel, immediately explained this (again with his left-hemisphere-controlled speech center) as “and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.”This is a confabulation. The right hemisphere (which controls the left arm and hand) correctly points to the shovel, but because the left

How to Create a Mind – Ray Kurzweil

hemisphere (which controls the verbal answer) is unaware of the snow, it confabulates an explanation, yet is not aware that it is confabulating. It is

taking responsibility for an action it had never decided on and never took, but thinks that it did.

Ray also discusses the quirks of free will and the problem of determining how to “proof” consciousness. In numerous experiments (the most famous is the Libet one), when the research group had to make a simple decision such as whether they’ll like to have a coffee. It turns out that the motoric part of the brain raises activity even half a second earlier before the decision-making area of the brain gets stimulated. This means that the body is already preparing the movement for grabbing the coffee before the aware decision is made, thus implying our free will is limited and we act as complicated state machines, not fully aware of the reasons behind our actions.

I find the consciousness theory part the most interesting. Kurzweil briefly describes the two consciousness theory by David Chalmers.

Chalmers does not attempt to answer the hard question but does provide some possibilities. One is a form of dualism in which consciousness

per se does not exist in the physical world but rather as a separate ontological reality. According to this formulation, what a person does is basedon the processes in her brain. Because the brain is causally closed, we can fully explain a person’s actions, including her thoughts, through itsprocesses. Consciousness then exists essentially in another realm, or at least is a property separate from the physical world. This explanation doesnot permit the mind (that is to say, the conscious property associated with the brain) to causally affect the brain.

Another possibility that Chalmers entertains, which is not logically distinct from his notion of dualism, and is often called panprotopsychism, holds that all physical systems are conscious, albeit a human is more conscious than, say, a light switch.

I tend to agree with the second theory that everything is conscious ‘to its own measure’, however, most of the subjects are simple. A light switch is ‘conscious’ of its two states (on/off). An ant is conscious of its closest surrounding, able to move based on inputs that come to its brain and perform logical operations such as to eat, to fight or to run (ant example is even more interesting by the fact for it seems a hive of ants is more intelligent and ‘aware’ than a single representative). A fish then is more conscious than an ant because of the more advanced decision-making system and event more inputs that it can accept and process at a given time. Then we move to mammals such as dogs, which have dreams, can solve simple logic problems, have more diverse and even more advanced brain. However, most experiments proof that dogs are unaware of their reflection. Well, human beings until the age of 2 can do neither, however, we learn that by observing a mirror and using our cause-and-effect system to link our movements with the reflection movements and eureka! comprehend our own reflection. Interestingly, chimpanzees, having a brain which almost resembles ours, can do that too.

We usually think of insects as mechanical constructs, by virtue of the rather simple and transparent logic they follow. Yet while rejecting consciousness of dogs or chimpanzees, we find some of the human traits in them, because we tend to interpret their actions by wrapping them with human intentions. However, if there was a machine or an organism 100 times more intelligent than humans, what would it think of us? Driven by desires, fears, hunger etc. which all stem from chemical reactions. Vessels armed with really complex (from a human perspective) processor, pattern-recognizer and uncertainty-based decision-making system? Wouldn’t it find our actions semi-automatical? If we were able to completely disassemble the brain, tracking each signal bit by bit, wouldn’t we found ourselves just the executors of some greater, reversed entropy, which drives spiders to weave their nets?

Summary

Overall, the book is a great brain teaser, however, one thing I find unnecessary is the chapter containing riposte for the critics of Kurzweil works. I may only wonder why Kurzweil decided to include those in this book. Nevertheless, I appreciate the world blooming with writings like this one.

Summa Technologiae – Stanisław Lem

It’s 1964, one of the greatest Polish science-fiction writers and futurologists is about to finish his latest book called “Summa Technologiae”. The name refers to the “Summa Theologiae” by Thomas Aquinas, which in the 13th century was the compendium of all the main theological teachings. It summed up the current state of knowledge. Similarly, in the middle of 1960s Lem sets off to a meta-journey to recon the world of technology, armed only with his intellect bounded by the restrictions of the Iron Curtain.

To approach this book without consideration of its historical and geopolitical background would be inappropriate. Moreover, hardly could we appreciate the charm of the writer, who, 26 years before the Internet became public, foresaw that for people to become a singular intelligent organism they would need “some kind of telephone” for sharing information globally…

Code Complete – Steve McConnell

In this short review, I’ll try to distill key features of this over 900 pages book.

Simply speaking, if the Clean Code by G. Martin is the “what”, this book is the “how” of programming practices. It covers key areas of daily programming tasks from problem definition, through planning, software architecture, debugging, unit testing, naming to integration and maintenance.

Is Introduction to Algorithms a good starter?

There are many different approaches to learning algorithms and data structures. However, I’d divide those into two sets: theoretical and practical with all kinds of in-betweens. When I faced this dilemma, I noticed that the most often called title was the famous Introduction to Algorithms by Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ron Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Reading and working through this book took me three months. Let me answer the given question: is Introduction to Algorithms a good starting book for learning algorithms and data structures?

The Shallow – Nicolas G. Carr

I came by this book by accident. Found it laying on a seat in a coach going to the Italian Alps. I decided to give it a try for two reasons. Firstly, I’ve heard about the book and it struck me it was the finalist of the Pulitzer Prize. Secondly, I noticed increasing difficulty in maintaining attention while reading myself. What I hoped to be a winter romance, ended up as a single serving friend, leaving rather mixed feelings.

Why? The topic itself is really interesting and more current than ever. However, the book seems like an essay extended to absurd lengths. Let me take up the challenge and present all the key ideas from The Shallow in brief nine sentences. Here we go…

The book

In the history of mankind, there were three inventions that overhauled the way we think: the clock, the print, and the web. The human brain is neuroplastic and flexible – the most often we use any particular area, the more it grows its neural connections. Additionally, in case of emergency (accident, surgery), some parts can take responsibility for the others. Because of the amount of information we receive nowadays (study from 2009 showed about 34GB a day) we can notice a shift in the way of thinking. We tend to move from deep, focused and thoughtful sessions to multitasking and information skimming. This drove us toward difficulty with maintaining attention in situations that take more time and don’t flourish with stimulation ex. reading longer text forms. Finally, we started treating smartphones as extensions of our brain. It lets us store data, notifications, dates, guide us through a new town and much more. Since it reliefs brain from those tasks, it has a side effect of decreasing neural connections, which leads to difficulty in memorization, disorientation etc.

And there it is… I admit Carr did the homework and well documented every theory with convincing levels of example, mostly scientific research. Surely the way people interact with the Internet has changed and treating it as air, from which we breathe information may result in creating a shallower form of intelligence. The curse of abundance – too much data, too quickly, too divergently, too distractedly, too unassociatively, and with too much finality.

Conclusion

Reading The Shallow in 2019 surely won’t open your eyes. The theories became facts. So does the book became obsolete? Yes and no. Yes, because most of the information depicted in The Shallow as shocking is now taken for granted. And no – it’s more actual than ever as we tend to integrate stronger and stronger with mobile devices, constantly being attached to the web. Is this a bad thing though? It doesn’t make much sense to answer that question, it’s just inevitable.

Pro Git – Scott Chacon, Ben Straub

Welcome to the first part of the book project series. Without further ado, let’s get started

Undoubtedly, there are many books about

I picked it a few weeks before the company I work at decided to move from the SVN to GIT, making what’s supposed to be a huge step forward. It turned out it really was.

Through the first 100 pages, Ben explains the concept of git, which is a decentralized versioning system and underlines what distinguishes it from other versions systems i.e. SVN, CVS, and Mercurial. Additionally, the author covers a number of topics: git customization, setting up a git server, or repository migration, which may help you during git initial setup. Chapters are well structured, precise and thrift. Concepts are explained in a clear manner and easy to understand. The book helps newcomers with getting to grips with the concept of distributed work using branches and provides several user stories, which cover most of the daily usages of the versioning system.

It’s a great chunk to start with in order to build a solid base of knowledge. Even readers who are already familiar with the git mechanics may find something interesting and non-trivial like chapters covering the git internals. After reading Pro Git I felt comfortable enough to navigate toward the git official documentation with a lot more courage.

Personally, the most important takeaway was the function called bisect, which I didn’t know existed before reading this book. It got into my mind so deep I decided to immediately put it into action. In case you are not familiar with it, here’s a short explanation from the official documentation:

This command uses a binary search algorithm to find which commit in your project’s history introduced a bug. You use it by first telling it a “bad” commit that is known to contain the bug, and a “good” commit that is known to be before the bug was introduced. Then

https://git-scm.com/docs/git-bisectgit bisectpicks a commit between those two endpoints and asks you whether the selected commit is “good” or “bad”. It continues narrowing down the range until it finds the exact commit that introduced the change.

Using it along automated tests allows to quickly locate the commit that broke it, which may really speed up your work.

Would I recommend the book? Definitely, just bear in mind you can really skip half of it, if you are not interested in the migration, server picking, choosing a communication protocol, or the git internals. Otherwise it’s well worth your time.

The Book Project

I must admit being busy with my new position as C# developer I haven’t spend much time on my blog lately. It’s a high time to change it. I decided to challenge myself with a task of reading and reviewing 12 books (+ extras) that are more or less related to programming. Based on the most recommended books for programmers, I’ve prepared a list and decided to see for myself if they’re worth reading. Except for reviews I’m going to work through a few examples from each book that I find the most significant.

Here’s the list:

- Clean Code – Robert C. Martin

- Pro Git – Scott Chacon, Ben Straub

- Head First Design Patterns – Eric Freeman

- 97 Things Every Programmer Should Know – Kevin Henney

- Introduction to Algorithms (parts)

- Cracking the Code Interview – Kitoyana

- How to Create a Mind – Ray Kurzweil

- The Shallow – Nicolas G. Carr

- Thinking, Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman

- Code Complete – Steve McConnell

- Clean Architecture – Robert C. Martin

- Refactoring – Martin Fowler